Dredging & Dumping

Sediment is an essential, integral and dynamic part of the ecosystem. Over 99% of sediment dumped at sea is locally-generated and results from the dredging of harbours and their approaches to ensure they are navigable. Most dredged material is dumped at established sites. It is also used for purposes such as beach nourishment or land reclamation. Fish wastes - material resulting from industrial fish processing operations from either wild stocks or aquaculture - and inert material of natural origin, for example rock and mining wastes, are also sometimes dumped at sea. Fish waste is only dumped in small amounts and at a few sites (fewer than 1000 tonnes per year). The phasing out of several types of waste disposal has reduced pressure on the marine environment. Dumping of sewage sludge and of vessels or aircraft has been banned by OSPAR since 1998 and 2004, respectively. Dumping of radioactive wastes has been prohibited since 1999.

Trends in dumping and dredging

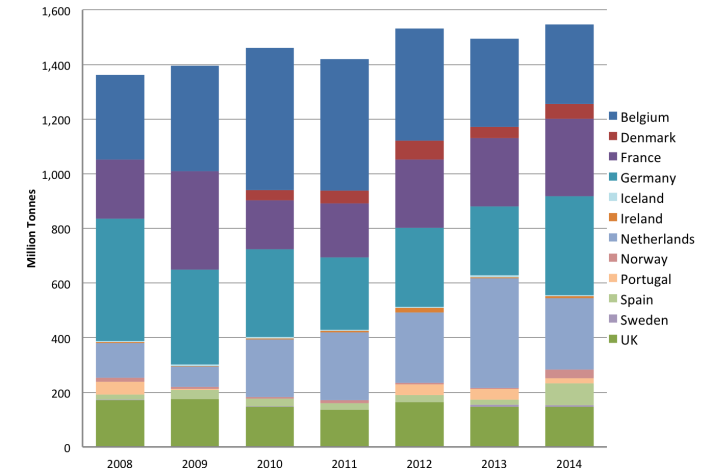

The most recent assessment of dredged material, for the period 2008–2014, was undertaken as part of OSPAR’s 2017 Intermediate Assessment of the state of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic. Over one thousand million tonnes of dredged material were deposited in the OSPAR Maritime Area during this time. This value includes material from capital and maintenance dredging.

Total amounts, in million tonnes, of dredged material deposited in the OSPAR Maritime Area per country over the period 2008–2014

Total amounts, in million tonnes, of dredged material deposited in the OSPAR Maritime Area per country over the period 2008–2014

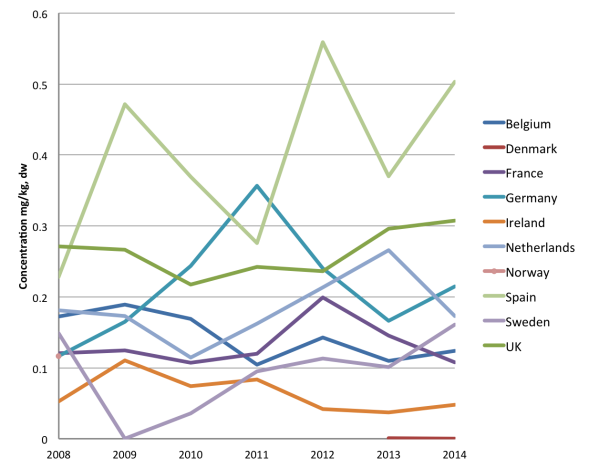

Average contaminant concentrations and total loads per country were calculated for cadmium, mercury, lead and tributyltin (TBT) for the period 2008–2014. Changes in total dredging quantities and total contaminant loads are dependent on external factors, including variation in sediment siltation rates due to storm events.

The calculated average concentrations, in mg/kg, dry weight (dw), for the trace metals are comparable to those described in the OSPAR Quality Status Report 2010. Although yearly fluctuations can be seen, there do not appear to be any meaningful increases or decreases across the entire assessment period. Annual average mercury concentration varied between 0.17 and 0.23 mg/kg. These values are almost identical to those reported for mercury in the previous assessment period 2003–2007 (0.18–0.22 mg/kg).

Figure 2: Annual average calculated mercury concentration (mg/kg, dw) in dredged material deposited in the OSPAR Maritime Area

Figure 2: Annual average calculated mercury concentration (mg/kg, dw) in dredged material deposited in the OSPAR Maritime Area

Beneficial use of dredged material (such as for beach nourishment and sediment recharge) has been monitored by OSPAR since 2013. This short period does not allow for trend analysis. The amounts for 2013 (28 million tonnes) and 2014 (37 million tonnes) are comparable; for both years beneficial use was implemented at approximately 80 sites. The most frequent reasons for beneficial use are beach nourishment and sediment recharge.

Environmental impacts of dumping and dredging

One of the main concerns over dumping and dredging is the release of contaminants to the water column (such as heavy metals and TBT), which is associated with temporary increases in turbidity. This can lead to increased availability of contaminants to the food chain. Contaminants in dredged material are monitored and assessed against action levels to help reduce pollution at dumpsites. There was a clear fall in contaminant concentrations in dredged material from the southern North Sea throughout the 1990s. This trend has since stabilised. In the Netherlands, TBT concentrations in dredged material have fallen since monitoring began in 1998. A further decrease in TBT concentrations is likely following the global ban on TBT-based anti-foulants. Nutrients released from dumped dredge spoil may contribute to eutrophication, but this will generally be of minor significance.

Knowledge about the effects of dredged material disposal on the wider environment is mainly from studies at individual dumpsites and from EIAs. Sediments are part of the marine environment and relocation of non-contaminated sediments to the sea supports the natural processes of the sediment balance. Increased turbidity may also lead to short-lived effects on organisms that are light-dependent, but these are generally considered to be negligible. Dumping sediments on the seabed may smother and crush organisms living on the seafloor and may cause changes in benthic habitats and biological communities. Changes in community structure are restricted to within 5 km of the dumpsite. Continuous maintenance dredging often takes place where navigation channels to ports have high sedimentation rates, such as in estuaries. Areas that are frequently dredged have a permanently changing benthic environment. Dredging in estuaries to create a new harbour, berth or waterway, or to deepen existing facilities, can affect tidal characteristics which may affect sensitive habitats. Dredging and dumping activities also contribute to underwater noise.

Management and regulation

Dredging and the dumping of waste and other matter have been well-regulated since the Oslo Convention came into force in 1974. OSPAR guidelines specify best environmental practice (BEP) for managing dredged material, with the most recent version adopted in 2014 (OSPAR Agreement 2014-06). National authorities use these guidelines to manage dredging and dumping and to minimise effects on the marine environment. The main management tools are licence and control systems. These require assessments of the environmental impact of planned disposal activities in relation to a specific dumpsite, sediment characteristics and contamination load. Since 2000, assessment and licensing procedures for dredged materials in most OSPAR countries have included action levels for contaminant loads based on the OSPAR guidelines. Since 1998, OSPAR has also had guidelines for the dumping of fish wastes.

Management of dredged material should respect the natural processes of the sediment balance. Selecting the appropriate location for a dumpsite is essential to minimise environmental impact. Several dumpsites have been relocated by applying the OSPAR guidelines. A planned site in the Weser estuary was relocated after a site survey detected a mussel bank. Dumpsites have also been relocated or closed to avoid impacts on MPAs, fisheries and shipping. The ban on dumping vessels or aircraft has been implemented successfully.

Existing regulations, including EU legislation, need to be fully implemented and their effectiveness evaluated before additional OSPAR measures are developed. Improved understanding of the effects of dredging and dumping activities on marine ecosystems, including in combination with other pressures, is needed. In recent years there has also been more focus on using dredged material for beneficial purposes, such as for protecting the stability of coastal and shelf systems.